What etiology of chronic abdominal distention?

A 53-year-old G2P2002 female with a medical history of hypothyroidism presented to her PCP for abdominal distention for three years. The patient endorsed occasional bilateral abdominal pain that she described as dull. She reported that it occurred randomly without specific provocation and was worsened by prolonged immobilization. It was not associated with nausea or vomiting, and she reported that was having normal bowel movements. Her menstrual cycles were normal with her last menstrual period the week before presentation.

She denied any unintentional weight loss, fevers or night sweats. Over the past several days her abdomen had become increasingly distended and was putting pressure on her ribs which prompted the PCP visit.

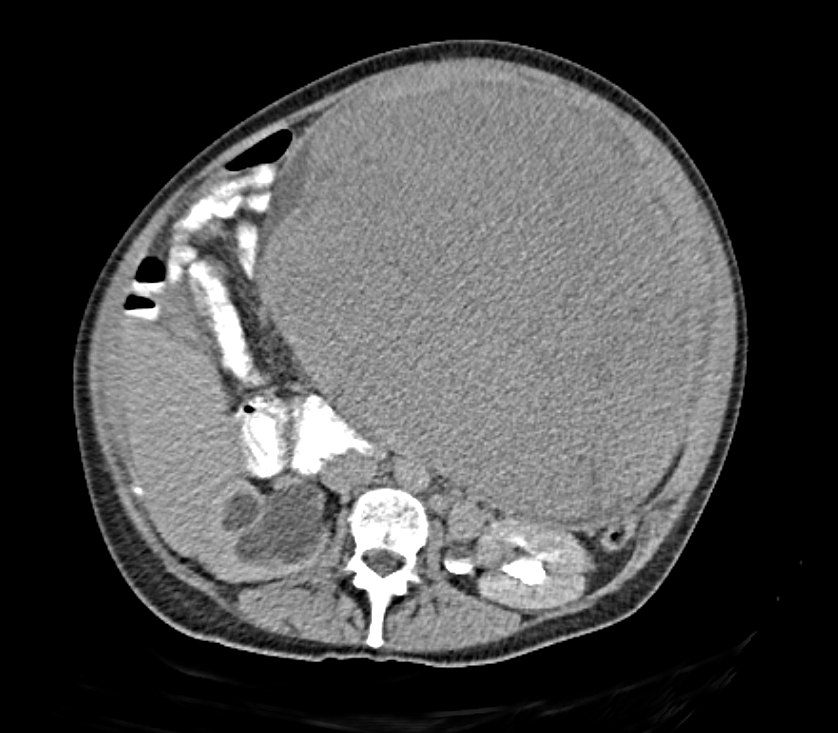

An outpatient CT (figures 1a-b) revealed “a 28 x 19 x 32cm mass arising from the pelvis and extending almost to the level of the diaphragm.” Radiology was unable to differentiate ovarian versus uterine origin of the mass. She was also noted to have severe right sided and moderate left sided hydroureteronephrosis. She was sent to the local emergency department (ED) and then transferred to our ED for further evaluation.

Figures 1a-b: Abdominal/pelvic CT: demonstrating an 28 x 19 x 32cm mass arising from the pelvis and extending almost to the level of the diaphragm as well as severe right sided and moderate left sided hydroureteronephrosis.

Figures 1a-b: Abdominal/pelvic CT: demonstrating an 28 x 19 x 32cm mass arising from the pelvis and extending almost to the level of the diaphragm as well as severe right sided and moderate left sided hydroureteronephrosis.

On exam, the patient was uncomfortable but in no acute distress with normal vital signs. She was noted to have a firm, bilobed mass that was palpable from the suprapubic area extending proximally to the xiphoid process with associated abdominal distention (figure 2). Her abdomen was not tender to palpation. Ob/gyn was consulted and noted that on pelvic exam she had a small cervix that was “elevated beyond the pubic symphysis” but had no obvious cervical tenderness nor adnexal mass.

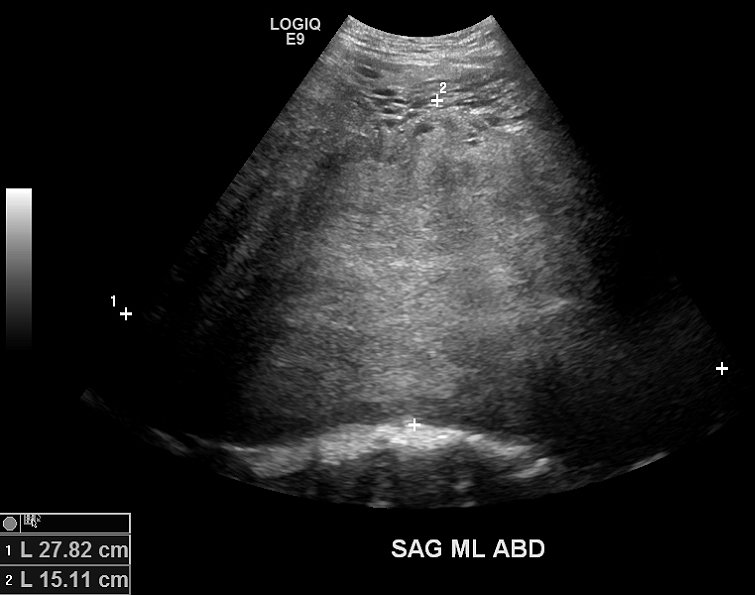

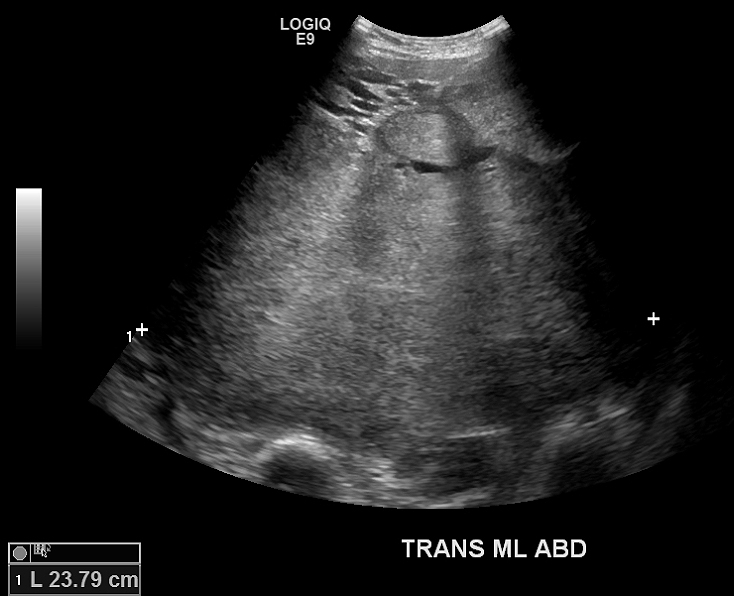

An ultrasound was performed which revealed a heterogenous echogenic mass involving the pelvis and abdomen that was unable to be measured (figures 3a-b).

Labs were significant for an AKI with a creatinine of 1.40 and GFR of 43, mild anemia with H/H of 9.2/28.4 but the remainder of CBC, LFT’s, and lipase were normal.

Tumor markers including CA 125 and CA 19-9 were normal at 23.6 and 14, respectably. AFP was normal at 0.9 as well as DHEA-S at 173. Her Hcg was undetectable.

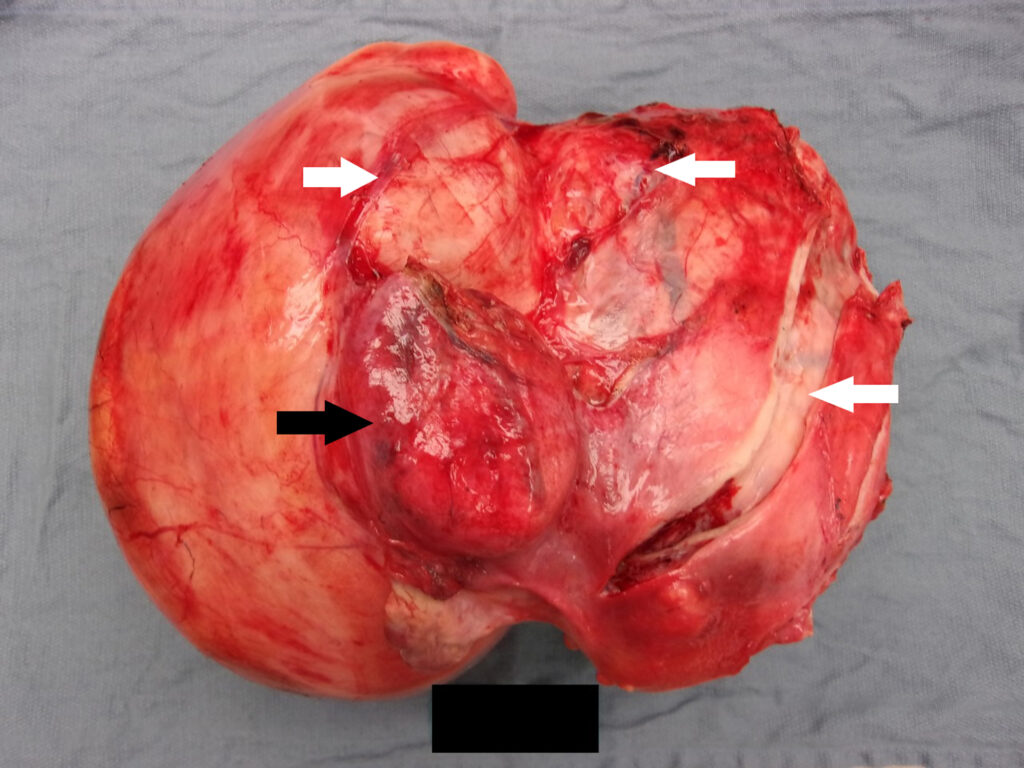

The patient was admitted and underwent a total abdominal hysterectomy with a salpingo-oophorectomy as well as an exploratory laparotomy. She was found to have a massively enlarged uterus extending from her pelvis to the xiphoid process with multiple dilated vessels feeding the mass. Her uterus was noted to weigh 48.4kg (normal uterine weight 0.05kg). Surgical pathology noted no pathologic changes of the cervix and bilateral fallopian tubes but multiple, large and bulky leiomyomatas of the myometrium (figure 4: black arrow cervix; white arrows fibroids).

Uterine fibroids (including leiomyomas or myomas) are benign uterine neoplasms composed of tumors of the uterine smooth muscle cells that are commonly found in women of reproductive age as well as in post-menopausal women. [1,2] They are the most common uterine neoplasms. [4] They can be single or multiple and are classified based on their location within the layers of the uterus (subserous, intramural, submucous) [2]. The major common risk factors in fibroid formation include both African American race as well as increased age to menopause. [3]

Figure 4: pathological specimen enlarged uterus with large and bulky leiomyomatas of the myometrium; black arrow cervix; white arrows multiple fibroids

Fibroids can be symptomatic or asymptomatic.

Symptomatic fibroids lead to numerous symptoms including symptomatic anemia from heavy or prolonged uterine bleeding, pelvic pain and pressure, infertility, painful menses, recurrent miscarriage and more. Women can also develop what is described as “bulk symptoms” which our patient was experiencing. These include abdominal distention as well as bowel and bladder dysfunction from an enlarged uterus. [1]

Fibroids can be diagnosed by multiple imaging modalities. Often, they are first suspected in premenopausal women who report heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding or when an enlarged uterus is appreciated during a pelvic examination. [1] Ultrasound, both trans abdominal and transvaginal, is often the first confirmatory imaging performed as they are inexpensive, easily accessible and differentiate fibroids from an adnexal mass or pregnant uterus. [1,2]

However, ultrasound is very operator dependent. [2] Large fibroids, such as those seen in our patient, can cause obstruction of the ureters leading to secondary hydronephrosis. Thus, ultrasounds should also include the urinary tract. [4] Gadolinium contrasted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to differentiate devascularized fibroids as well as the relationship of fibroids to the endometrial and serial surfaces which is helpful in determining the best treatment option for the patient. [1] When ultrasound is unable to determine the origin of a pelvic mass, MRI evaluation should be performed. In fact, MRI is the preferred imaging modality for the characterization of fibroids as well as determination of their anatomic location. At times, fibroids can also be found incidentally on CT imaging performed for other indications, but CT is not the imaging modality of choice. [4]

Treatment is guided by the symptoms a patient is experiencing as there is no evidence supporting treatment of asymptomatic fibroids. The most commonly reported presenting symptom is abnormal uterine bleeding. [2] Potential treatment options include hysterectomy as well as uterine-sparing interferons such as myomectomy, hormonal contraceptives, uterine artery embolization, and endometrial ablation. [1]

References:

- Stewart, Elizabeth: Uterine Fibroids. N Engl J Med 2015; 372:1646-1655

DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcp1411029 [https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMcp1411029?casa_token=9cX3vM7jqZEAAAAA:rZh1qPL5po5CQACOfJqtMfx8YwebWeCnpbtleoPLFdU34zNlei0gc7_Q8KqxuzsetBq-dQasw7DPmWM] - Khan A, Shehmar M, Gupta J: Uterine fibroids: current perspectives. Int J Womens Health 2014;6:95-114. DOI: 10.2147/IJWH.S51083 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3914832/]

- Marshall LM, Spiegelman D, Barbieri RL, et. al. Variation in the incidence of uterine leiomyoma among premenopausal women by age and race. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:967-973

- Wilde S, Scott-Barrett S. Radiological appearances of uterine fibroids. Indian J Radiol Imaging 2009;19(3): 222-231. DOI: 4103/0971-3026.54887 [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2766886/]

1 Comment

Not that it would affect the ED disposition or care, but when was her last pelvic exam ?