“Inspiration exists, but it has to find you working”—Pablo Picasso

Background

The Syrian Civil War began nearly nine years ago and continues to have reverberations to the region with millions of displaced refugees in neighboring countries. Jordan, a land-locked country in the Middle East has long accepted its share of refugees from regional conflicts.

We spent a week treating Syrian refugees in June 2019. Our local partner was Dr. Ahmad Al-Khatib, who with his wife, Anne, runs the Human Doctor project from their home in Germany. The project does a major outreach every Spring in partnership with the Flying Doctors of America to help the Syrian refugees get medical care. Dr. Al-Khatib recruits colleagues of his from Germany to come volunteer and also involves approximately 30 Jordanian medical students each clinic day to help translate Arabic to English and to see patients with us.

The Work and the People

Our journey started each day from Amman, the capital city of Jordan. Eighty kilometers north was the town of al-Mafraq, which is just south of the Syrian border. In Arabic, the translation of the town name means “crossroads.” Our crossroads was that of many meanings—travelers meeting from around the world to help those in need, young medical students in Jordan growing up watching refugees migrate and the thousands of refugees themselves now, truly, stateless. We ran our clinic inside a madrassa (school) 10 kilometers south of the Syrian border.

The largest refugee camp, Zaatari, estimated to house 70,000 Syrians (at the time of this article) was approximately 25 kilometers away.

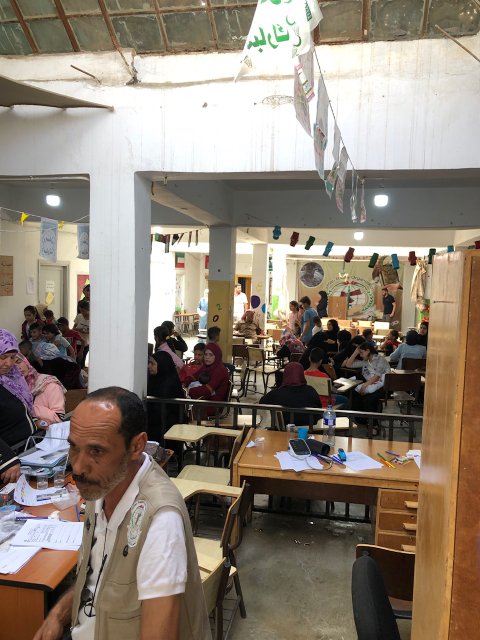

The second floor of the school had approximately eight classrooms that we partitioned into various “clinics”— internal medicine, surgery, women’s health, pediatrics, pharmacy, orthopedics and wound care. We had a mixture of internists, emergency medicine and other providers both from the US and Germany, as well as our Jordanian medical students and one US medical student, Onkur. Patients would come directly from al-Mafraq or surrounding towns via bus to the school, walk upstairs and right at the stairwell get triaged by vitals and chief complaint. Each patient was given a history and physical exam sheet and sent to wait in front of the respective clinic for the provider.

Our first day, I ended up running the women’s health with an ER nurse, Sarah, and helped oversee the pediatrics clinic run by Woan-Sa, an ER nurse; Eric, an EMT and Cody, an emergency medicine PA.

As with prior missions, I quickly gravitated towards marshalling resources and time to help pregnant women and sick kids. We were able to obtain a mattress and pillows to set-up a cursory exam table for basic obstetrics ultrasounds using the Butterfly iQ. It was a great opportunity to show the local Jordanian students a new technology and help mothers see pictures of their babies for the first time. No matter how many times or in how many countries I do this, it still leaves an indelible mark on me.

Several of the children we saw the first few days were quite malnourished and many were febrile. In nearly 100 degree ambient temperatures, it can be hard to distinguish a sick child from simply one that is overheated. Sarah showed incredible astuteness in recognizing febrile children with old school nursing instinct and “the eyeball test.”

Some of the children we did see during the week were complex, logistically challenging cases to manage. Several had poorly healed long bone fractures from war related injuries.

One case that stood out was a 10-year-old boy with a recent hot water burn to his abdomen. To me, there is no more helpless feeling as a doctor than when you see a condition you know you can treat, but don’t have time, resources or money to fix. Thankfully, last minute, I had brought some silver-based dressings to help cover and dress his wound.

After that case, suffice to say I won’t forget packing or bringing burn dressings on all future humanitarian trips.

One of the most remarkable points of this trip was our bus ride home after day 1 of the clinic. We had treated 500-600 patients as a team and were exhausted, but led by Dr. Al-Khatib, we stopped by to visit a small satellite refugee camp he encountered on his own travels.

This camp was holding about 120 families (with lots of children) in a broad stretch of desert with nothing in either direction for miles. We met with some of the village elders and heard about their struggles for clean water, food and medicine. Dr. Al-Khatib told us that at his last visit, as is custom, he had tea with the elders and tasted a drop of the water they were using. It was pungent, dirty and likely had high sulfur content.

This camp however, was resourceful and grew corn and tomatoes. They sold crops to establish trade with neighboring towns. The images of the harshness of that landscape and how human beings find ways to survive remained etched in my visual cortex the rest of the trip. After seeing the conditions, Ahmad made sure the buses that brought us patients stopped at this particular site every day.

Dr. Al-Khatib’s personal commiseration with the refugees was unparalleled to anything I have seen in a long time from a physician. I learned from my discussions with him that he was a refugee once and by perseverance and effort, he was able to attend medical school and ultimately, learn German. After passing German medical licensure tests, he moved there to work at a hospital, but he comes back with his wife to administer aid to the refugees annually.

Our second day was smoother as we had better group dynamics and efficiency. Because I had the ultrasound machine and a few other gadgets, I found myself bouncing back and forth between several rooms. It was quite an exhausting maze of patients, overcrowding, heat and difficult clinical decision making. As a group, we saw close to 2,400 patients in just four days working approximately 10 hour days.

Among the patients, one young boy, 10, stood out. He arrived having vomited recently — pale and ill-appearing with a fever to 102 degree and tachycardic. He was clutching his right lower quadrant and listless. We laid him down and I was concerned for peritoneal signs.

Earlier, I learned Cody and Eric brought a box of parenteral meds and IV fluids — based off their experience from having been on this trip previously. If ever there was a need to use those supplies, now was the time with this truly ill child. Eric deftly placed an IV. Sarah spiked a liter of fluids. Cody mixed up an antibiotic and anti-emetic as I verified weight, medication dosing and did a bedside ultrasound.

My ultrasound showed a possible dilated appendix and with Ahmad’s guidance we called for an ambulance. The child was taken to the only area hospital. His father came back to see us at the end of the clinic with an update. He showed me his son’s tests — they had done just a urinalysis and discharged his son. He was irate that the hospital didn’t listen to us. We calmed him down and then realized we had only one choice —keep treating him with antibiotics, antipyretics and have the boy come back to see us again. It was the end of a very long day and I made a judgment call to take a medical student, Khalid, and speak with the pharmacist.

Unlike the US, in Jordan, you can just purchase medications on the spot without a prescription. I rifled through several shelves until I found the two antibiotics I wanted. This was a time-consuming process since we had to translate most of the brand names back to generics so we could figure out the proper choice. As we paid and headed back to the clinic, I thought about how to resuspend the medications and write instructions in Arabic. Thankfully, our students helped.

I provided both antibiotics to the father, who was extremely grateful for our care and told us he would try to bring his son back in before we left town. Unfortunately, when you care for thousands of patients, follow-up becomes next to impossible. I looked for that boy each of the next two days and he never showed up again—hopefully, because he improved.

As our last clinic day unfolded, a familiar mixture of accomplishment with incompleteness fell over me. We had done so much, but so much more was left to be done. I took solace in the fact that Ahmad has made this a sustainable outreach and that the medical students all were extremely thankful and grateful for the chance to participate. I believe many of them will continue to reach out to those in need as they progress in their careers.

On our last two days in Jordan, to help decompress from the week, we visited Petra and the Dead Sea.

I cannot emphasize how important it is after such tough work to do some type of team exercise to unwind. For me, seeing anything historical always helps keep me grounded. Getting to see an ancient civilization like Petra and floating on the Dead Sea was a once-in-a-lifetime experience—to get to do it with such honorable, caring and hardworking colleagues was a bonus!

Afterthoughts:

I jotted down some other tips while we drove to Petra and the Dead Sea about planning and execution for large-volume clinics:

- Vitamins, toothbrushes, toothpaste, oral rehydration salts should be pre-packaged and given out to all patients or families as soon as they complete triage. Amoxicillin and anti-pyretics must be overstocked!

- Pharmacy distribution often becomes the main bottleneck—pre-filled medication sheets with instructions in both English and the most prevalent local language are essential.

- Taking inventory each day is helpful and necessary. Our Jordanian medical students tried so hard to do this and it was chaotic even with spreadsheets.

- Flexibility with regards to timing and resources is essential. I often survey the area around where we are seeing patients (Google maps and/or walking a few blocks in each direction with a host/guide are great places to start!) to get a feel for where a hospital, pharmacy or medical supply store might be, if we need their help.

- Adapt to the local standards of care—without compromising your clinical integrity. One example would be first learning how the local doctors would manage, say, heavy menses. In the US, we might do some labs, a pelvic exam, possibly an ultrasound and then a trial of hormones. That is not feasible on these missions. From prior trips to Muslim majority countries, I am aware this is a common chief complaint, but also one with limited ability for us to evaluate. So, I prepped my clinic team to rely heavily on vital signs and exams—looking for anemia (capillary refill, pale conjunctivae, pallor, etc.). Almost every female needed iron and vitamin supplementation so that was something we could do to offer help. Vitamins are quite expensive in Jordan and we ran out very quickly each day. We could not prescribe hormonal therapy or any type of contraceptive due to cost and cultural barriers, respectively. While there, I thought of something I learned in India, tranexamic acid (TXA) tablets. TXA is not the first go to standard in the US for menorrhagia, but it is FDA approved for it. I wish I could have gotten some to give to patients that met criteria since it is cheap and effective. I even asked the local pharmacy and they did not have it.

There are plenty of other examples of medical conditions you can anticipate you will see and try to be prepared to treat—asthma, palpitations, burns, eye complaints, come to mind. For asthma, I have purchased a battery-operated nebulizer machine that I now pack on every trip. For palpitations, I now carry the Kardia EKG with me. For burns, I now pack silver dressings and make sure we stock Bacitracin. For eye complaints, I bring a portable ultrasound. The main point I want to make is try to prepare for a “second best” option of diagnosis/treatment and match your supplies with the population you will be treating.

Special thanks: Flying Doctors of America, the Human Doctor Project and to all the medical student (and other volunteers) that allowed us to help in Jordan for the week!

Contributing Writer bios:

Ahmad Al-Khatib, MD is a practicing internal medicine physician in Germany and co-founder of the Human Doctor Project in Jordan.

Eric Paul is an EMT in Las Vegas, Nevada.

Cody Pulsipher is an emergency medicine PA in Utah.