Emergency medicine physicians and other emergency personnel are the gatekeepers for the hospital. We examine, test and attempt to diagnose all patients who come through the door. As disease patterns evolve, so too must we. Being aware of emerging illnesses and remaining diligent in identifying their presence ensures a safe environment for the patient and the community. Measles is a highly contagious and potentially lethal viral infectious disease.

In 2000, it was declared eradicated in the United States. It has since re-emerged, in large part due to a combination of the rise of the anti-vaccine movement and imported cases (from other countries with lower vaccination rates). Since Jan. 1, 2019, there have been 159 confirmed cases of measles in 10 states: California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas and Washington. For comparison, in 2018 there were 63 new cases of measles in the US for the entire year. Some areas have had to declare a state of emergency. Early identification in the ED is critical to minimize exposure and help prevent spread.

Transmission

Measles is caused by a Paramyxovirus and proliferates through coughing, sneezing and contact with contaminated surfaces. It lives in an airspace where the infected person coughed or sneezed for up to two hours. If others breathe the contaminated air or touch the infected surface, then touch their eyes, nose or mouth, they can become infected. The average time from exposure to the virus to development of a rash is 14 days, but can range from 7-21 days. According to the CDC, if one person is infected with measles, 90% of the people close to that person who are not immune will also become infected. Patients are considered contagious from four days before the onset of the rash to four days after the rash’s onset. It cannot be overstated: early identification in the ED is important so that the patient can be immediately isolated from other individuals in the department. Consider measles in the differential diagnosis of any patient with fever and a rash.

Symptoms and signs

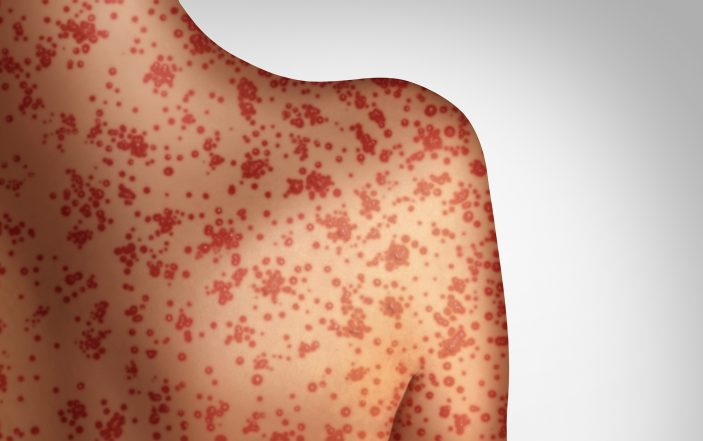

Measles is characterized by a prodrome of fever, malaise, cough, runny nose and conjunctivitis. The fever has been reported as high as 105oF. The prodrome is followed by a maculopapular rash that usually begins on the face. It spreads from head to trunk, then to the lower extremities — and often involves the hands and soles of the feet. Note that some immuncompromised patients may not develop a rash. Koplik’s spots are pathognomonic for measles. They typically appear as clustered white lesions on the buccal mucosa opposite the upper first and second molars and manifest two to three days before the measles rash itself.

Since the typical measles rash may not appear for up to four days, symptoms of early measles can be mistaken for influenza. There are some distinguishing features of the illness that should raise concern: recent international travel or contact with an international traveler is more frequently reported in cases of measles. Conjunctivitis and sensitivity to light is part of the prodrome of measles, but is not classically seen in those afflicted with influenza. Koplik spots, when present, are usually identified prior to the rash of measles and again are pathognomonic for the illness.

Vaccination

The first dose of MMR vaccine is given between 12-15 months of age, and the second dose is given between four- and six-years-old. Persons who are vaccinated are more likely to have a milder form of the disease and are less likely to be contagious. Receiving both doses confers 97% immunity while one dose is considered 93% effective.

Anti-vaccine movement

In 1998, the journal Lancet published a study involving 12 children with a history of developmental disorder and intestinal symptoms. In eight of these children, the onset of behavioral problems was linked with MMR vaccination. The authors essentially claimed to have identified a new syndrome of “autistic enterocolitis,” raising the possibility of a link between a form of bowel disease, autism and the MMR vaccine.

Despite the paper claiming that all 12 children were ‘previously normal,’ five had documented pre-existing developmental concerns. In nine cases, unremarkable colonic histopathology results were later changed to ‘non-specific colitis.’ In 2004, it was revealed that the primary author of the study, Andrew Wakefield, had been paid by a law firm that intended to sue vaccine manufacturers – a conflict of interest he failed to disclose. He had also patented a separate measles vaccine. In 2005, Lancet retracted the entire study after an independent government review concluded that Wakefield had acted ‘dishonestly and irresponsibly’ in conducting his research.

In 2010, he was banned from practicing medicine in the UK. Despite this, fears regarding a link between autism and vaccination persevered. While campaigning in 2008, then-candidate Obama said: “We’ve seen just a skyrocketing autism rate. Some people are suspicious that it’s connected to the vaccines. [Gestures to an attendee] This person included.” President Donald Trump has written “Massive combined inoculations to small children is the cause for big increase in autism…”

Complications

Approximately 1 in 20 persons afflicted with measles will be diagnosed with pneumonia, and this is the most common cause of death in such patients. Overall, approximately 3 patients for every 1,000 will die. Other complications include otitis media, encephalitis and seizures. Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis (SSPE) is a rare complication that may develop 7-10 years after the infection. SSPE is a progressive neurologic disorder associated with mental decline and seizures. Most patients die within three years.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is best made via serologic tests and a nasopharyngeal or throat swab. Urine may contain the virus and testing the urine increases the likelihood of detection. Patients who have received an MMR vaccination in the previous 6-45 days may present with falsely positive IgM levels. Diagnosis is confirmed if the PCR test is positive (a negative PCR does not rule out measles), IgM levels are positive and IgG seroconversion has occurred or there is a significant rise in measles titers. Ideally, one should be able to directly link the infected patient to a confirmed case.

Management

When there is a high degree of clinical suspicion, patients should be placed in airborne isolation as soon as possible. Undertake best efforts to avoid exposing the waiting room or other members of the healthcare team. Place the patient in a mask, utilize a negative pressure isolation room if available, and have all providers wear an N95 respirator at a minimum. Protective gowns, gloves and caps are encouraged as well. All states require patients with the diagnosis of measles to be reported to the local health department.

Patients who have come into contact with someone potentially afflicted with measles should receive an MMR vaccine if one was not administered within the previous 72 hours. Immunoglobulin should be administered to those who are less than 12 months of age, pregnant women and the severely immunocompromised.

Infants less than six months of age cannot receive the MMR vaccine and should only receive immunoglobulin. Unfortunately, with more people declining vaccinations for their children, herd immunity has decreased and others are unnecessarily placed at risk. Measles immunization is the key to prevention of this potentially fatal illness.

Clarification: In the statement attributed to Mr. Obama, he was gesturing to an attendee while saying “this person included.” Mr. Obama was not referring to himself in that statement.