Is a low threshold for contrasted abdominal imaging for patients following virus recommended?

Background

Thrombotic complications are a common presenting complaint in COVID-19 associated illnesses. This case report details the presentation and management of a patient who presented with splenic infarction after being discharged following diagnosis with COVID-19.

Introduction

Abdominal pain is a common presenting complaint in the ED with a wide differential diagnosis. History, risk factors, appearance of the patient and examination play a vital role in determining laboratory workup, imaging and a diagnosis. Patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 may have elevated risks for vascular causes of abdominal pain (1) and we describe one example of this.

Case Report

A 59-year-old man with no history of diabetes, vascular disease, smoking or abdominal surgery presented to the ED with three days of dull left upper quadrant pain without any radiation, nausea, vomiting, fever or diarrhea. He was hospitalized for three days with a diagnosis of laboratory confirmed COVID-19 associated pneumonia and hemoptysis without intubation and had been released eight days prior. During the hospitalization, his CT of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolus. He declined remdesivir or convalescent plasma, and was discharged on dexamethasone and doxycycline.

On physical examination he was afebrile, BP 157/101, HR 78, and a pulse oximetry of 100 percent on room air. He appeared mildly uncomfortable with moderate tenderness in the left upper quadrant without rebound or guarding.

Laboratory evaluation was remarkable for a WBC count of 23 x 10(3)/mm3. His lipase, hepatic panel, electrolytes and creatinine were normal. His blood sugar was 200 mg/dL.

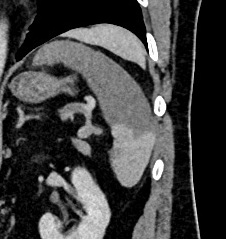

Contrast enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a geographic area of hypoenhancement of the spleen (Figure 1) consistent with a splenic infarct. On coronal reformats (Figure 2) a small thrombus was identified within the distal splenic artery.

Hematology consult was obtained by telephone in the ED and it was recommended that the patient undergo IV heparin therapy as an inpatient given that the splenic infarct was acute and symptomatic. Further laboratories ordered included a D-dimer of 2.88 ug/ml and Fibrinogen level of 602 mg/dl, which were available at the time of ED visit. Laboratories ordered in the ED, which came back during the inpatient stay were anIL-6 level of 345 pg/ml and a thrombophilia panel, which was negative for Prothrombin mutation, Lupus anticoagulant, Antithrombin III deficiency and Factor V leiden.

Additionally, thromboelastographic testing was performed after the patient was started on heparin therapy. This viscoelastic testing demonstrated the patient to have normal clotting function, including normal time to clot initiation (R value eight minutes)[normal two to eight minutes]and normal clot strength as demonstrated by the MA (59mm)[normal reference range 51-69].

However, the patient demonstrated very little clot break down–1.1% at 30 min. As has been suggested in other publications, this diminished clot lysis may be one of the reasons that patient’s with COVID-19 are having thrombotic complications.[1] This patient’s viscoelastic testing and thrombophilia work up were in all other ways essentially normal. Further speculation as to why the virus or the body’s response to infection may inhibit normal clot lysis is being further explored, [2] but likely hinges on imbalance between plasmin activation and inhibition.

Ultimately the patient was discharged without complication three days later on Enoxaparin daily at home and required no further hospitalizations.

Discussion

Thrombotic complications of COVID-19 are an emerging topic in recent literature. [3,4] Some authors suggest using D-dimer as a screening tool for assessing the risk of thrombosis in these patients. [4] During this patient’s prior hospitalization, his D-dimer was 1.26 ug/ml, which rose to 2.88 ug/ml on ED admission and peaked at 5.36 ug/ml during the second hospitalization.

D-dimer is frequently elevated in COVID positive patients therefore decreasing its effectiveness in predicting clots in these patients. [5] Thromboelastographic (TEG) analysis can instead be used to predict hypercoagulability. A prior study of COVID positive patients revealed that patients who experienced two or more thrombotic events versus patients who experiences less than two events had statistically higher maximal amplitude (MA) values on TEG analysis. [6] This difference existed even in the absence of statistically significant variations of partial thromboplastic time, prothrombin time, INR and platelet levels between the two groups. Thus, TEG can be relied on to reveal risk for thrombosis even when more standard labs fail to do so.

Heparin was used to treat the thrombotic event in this case due to its short half-life. The patient was then transitioned to a Low-Molecular Weight Heparin at discharge. Direct anticoagulants, such as Apixaban and Rivaroxaban may not be preferable in COVID-19 patients recently on dexamethasone given that it can induce CYP3A4 and the interaction with these anticoagulants is yet unknown.[7]

We recommend a low threshold for contrasted abdominal imaging in patients with recent COVID-19 infection and abdominal pain without a defined cause.

References

- Wright FL, Vogler TO, Moore EE, Moore HB, et al. Fibrinolysis Shutdown Correlation with Thrombotic Events in Severe COVID-19 Infection. J Am Coll Surgeons. 2020; 231(2): 193–203.e1 PMID: 32422349

- Medcalf, RL, Keragala, CB, Myles, PS. Fibrinolysis and COVID-19: A plasmin paradox. J Thromb Haemost. 2020; 00: 1– 5. https://doi.org/10.1111/jth.14960

- Santos Leite Pessoa M, Franco Costa Lima C, Farias Pimentel AC, Godeiro Costa JC, Bezerra Holanda JL. Multisystemic Infarctions in COVID-19: Focus on the Spleen. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7(7):001747. doi:10.12890/2020_001747

- Cui S, Chen S, Li X, et al. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020; 18(6): 1421-1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [Epub ahead of print]

- Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID-19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033-2040. doi:10.1182/blood.2020006000

- Mortus JR, Manek SE, Brubaker LS, et al. Thromboelastographic Results and Hypercoagulability Syndrome in Patients With Coronavirus Disease 2019 Who Are Critically Ill. JAMA Netw Open.2020;3(6):e2011192. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.11192

- COVID-19 and VTE/Anticoagulation: Frequently Asked Questions. https://www.hematology.org/covid-19/covid-19-and-vte-anticoagulation. Accessed August 23, 2020.

2 Comments

I have been diagnosed with a splenic infarct and tested positive for COVID 19. I’m wanting to know any information and if the COVID caused the splenic infarct. Please email me.

I have just been diagnosed with a splenic infarct. I previously had Covid-19. I believe the timing of symptoms would indicate that the Covid-19 caused my splenic infarct.